To map these maneuvers as succinctly as possible: the introduction of an amoebic workshop into a gallery space reserves the potential for art’s becoming-animal on condition that the animal is dematerialized, rendered abstract, and recedes from – or even submerges – human consciousness.

We are in fact dealing with an ‘abstract Animal’ throughout this essay. If there is no ‘animal’ toward which art is directed, this suggests that the animal as such is deterritorialized or uncoupled from human consciousness. There is no animal – actual or symbolic – involved, only the uptake and release of molecular speeds, intensities, and modulations which are injected into art.

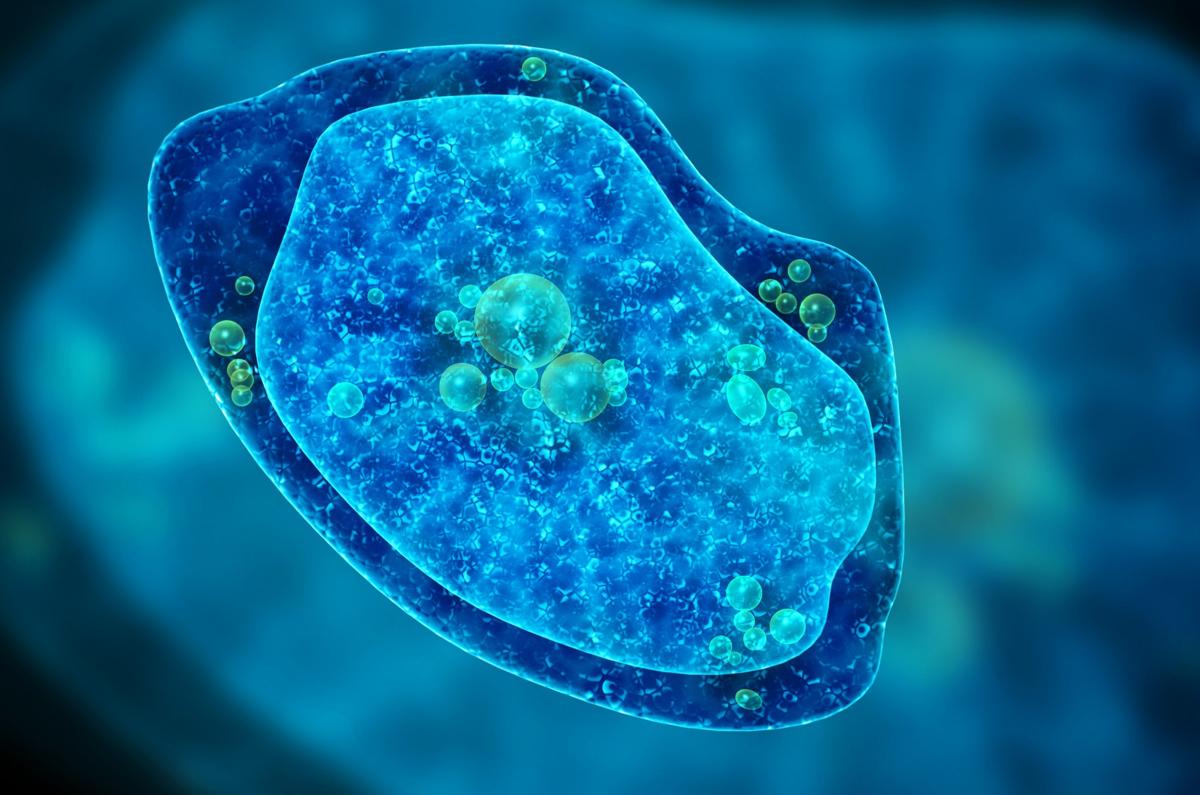

Art becomes highly dynamical, energetic, and unpredictable, since its becoming-animal does not entail a mimetic, or imitative, process. The subtle difference being evoked is that if the animal is proclaimed an artist, this does not trouble the coding of human epistemic values onto the animal, whereas to probe art’s potential to become animal is to delineate the action of an ungovernable, unpredictable mutation within art that resists subsequent recoding. Essentially, the potential for art to become animal resides in the disqualification of animal as artist. The refusal to apply the term ‘artist’ to the amoeba generates the necessary momentum for considering art as amoebic, and for enabling art to transcend its programmatic association with the human. Just as significantly, it asks whether our conception of the animal is capable of evolving when a space conventionally dedicated to human aesthetics is made host to a living, thriving system. Introducing a fragment of Mediolus corona’s lacustrine habitat into the gallery space for the first time in its 720-million-year history – without annexing or subordinating it to an artist’s oeuvre – instead poses the following question: toward what horizon can art be redirected once estranged from its prescribed associations to the human? The exhibition attempts to track whether the artworks of Drenk, Lalonde, and Wieser would ‘behave’ differently, would express different dimensions, when exposed to an inhuman living system. Such a statement would already betray a human-centered, correlationist, and anthropomorphic worldview. The Amoebic Workshop does not claim that Arcellinidas, or testate amoebas, are artists. By bringing the actual territory of the amoeba into proximity with contemporary art, and with artistic traditions such as the Renaissance workshop, the virtual territory that makes possible artistic expression reveals one of its oldest faces: that of Pseudo-amoeba. The transactions between life and matter at the micro-scale – on the other side of the vast abyss of space and time that separates our world from the world of ‘dirt’ – thus become, in this essay and its attendant exhibition, the means for reconceptualizing the processes underpinning human technē. Though invisible to the gallery visitors – who by design were denied any visual representation of the amoeba’s shells (tests) in the exhibition itself – the ‘exhibition’ of the amoebic workshop submerged within the milieu of the lake sediment was intended to draw attention to modes of creation and construction that escape not only direct perception, but also straightforward aesthetic categorization. These shell-building protists were housed in an aquarium set up by Carleton University’s Patterson Research Group (PRG), who had collected live samples of the micro-organisms from Bell’s Lake, Ontario along with other species of plant and animal life, and sustained them there within the sediment in which they naturally reside. Along with artworks by Jessica Drenk (United States), Gabriel Lalonde (Canada), and Claudia Wieser (Germany), the exhibition featured as its centerpiece a living culture of single-celled amoebas, Mediolus corona. This essay was largely written in concert with an exhibition I curated at the Critical Distance gallery in Toronto, Ontario, titled The Amoebic Workshop: A Submerged Exhibition, which opened on 21 September 2016.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)